When Newmarket became an incorporated village in 1858, a series of serious problems faced the new administration. The constant threat of fire and the contamination of our wells for drinking water contributed to numerous hazards of safety and health.

In 1862, plans were discussed to build a new town hall and market house, including hiring a competent engineer to draw up plans and give council an estimate on the cost to drain the village. The committee in charge reported a thorough system of waterworks should be installed. Those who still question the amount of water beneath our feet have not read about these studies done in the 1800s.

The prevalence of typhoid fever, diphtheria and small pox locally must not be disregarded — council had not forgotten the terrible disaster that had befallen the village with the numerous scourges of diphtheria during the previous year.

At the peak of previous epidemics, children from the entire district died. Parents were bereaved of two, three and, in some cases, the entire family. The two undertakers, John Millard and Samuel Roadhouse, were unable to cope with the situation. For reasons of health and safety, the little bodies were at once carried from their homes and without any ceremony laid to rest in Newmarket Cemetery, lying in rows of graves, mute evidence of that tragic time. If you walk through the cemetery today, you can see the evidence of these early scourges.

Typhoid fever and smallpox were frequent and recurrent visitors, a scourge dreaded by our citizens. Vaccination was made compulsory, pest houses were established and as soon as a case was reported, the victim was isolated.

There was no standardized sanitation. Council minutes from those years reveal that every effort was taken to keep the streets clean. Penalties were imposed on those householders who ignored the bylaws regarding the care of private grounds. Animals roamed at will and the filth of pig pens and chicken coops infested with rodents existed in a number of back yards. The forests had been removed and swamps and streams had become sluggish, open sewers.

When legislation proclaimed a Central Board of Health for the Province of Ontario, municipal councils were instructed to appoint a local board of health. The village council introduced one in a bylaw in April 1886 and the appointed members were Dr. J. J. Hunter, Dr. J. Hacket, Robert Simpson, Joseph Millard and James Pearson.

A public notice was posted in May 1886 that only suggested procedures for the removal of manure piles and decaying vegetation as possible sources of contamination, contributing to the spread of disease.

A bylaw for enforcement of sanitary conditions was enacted in 1884 and directives issued by the board of health attempted to control the problem of cleaning drains and open ditches by the use of lime in house and out-buildings. Wells were ordered to be enclosed to prevent rats, mice and other vermin getting into them. At this time, there were no indoor facilities or a central water supply.

Several dreaded diseases were prevalent and the only action that the doctors could take was to isolate and disinfect the premises with carbolic acid and chloride of lime. When a household was quarantined for diphtheria, typhoid fever, scarlet fever or smallpox, the front and back entrances were placarded to prohibit outside contacts. The placards were different colours for different diseases and continued in use until the 1930s.

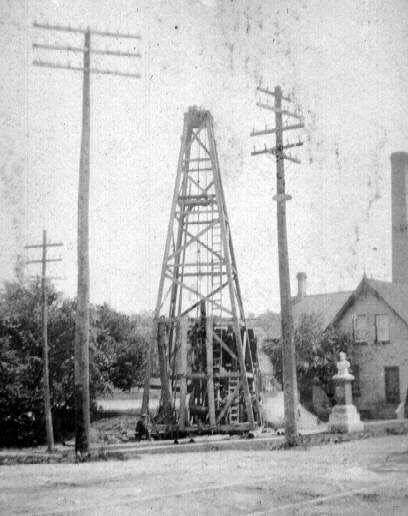

One of the reasons why I called Henry Stiles Cane one of the most forward-thinking mayors in our history was because of his decision to push forward with the instillation of the waterworks in 1915, a project which brought clean water to Newmarket households in the downtown area and the creation of two huge artesian wells to store fresh, clean water for the town. The days of getting your water from contaminated backyard wells was coming to an end. You can read my article Henry S. Cane one of town's most progressive mayors.

Adequate control of contagion was not effectively dealt with until Mayor Dales, a physician, forced the issue by the appointment of a public health nurse starting on Aug, 1, 1944.

The minute book of the board of health records state that in March through June 1873, a local family was treated for diphtheria. A resolution was passed at a public meeting to remove the people from the house and burn it down after they were relocated. The board of health overruled this decision as a wanton destruction of property and stated that by disinfection of the premises the diseases could be controlled. Amazing.

The control of public health depended on the preventive actions of individual citizens, the resident doctors and the local board of health. The provincial health department’s main concern was to receive “when convenient” the names of the local members.

An order-in council Sept. 29, 1888 further instructed the medical officer of health to notify the province of any cases of contagious diseases. Their mandate did not seem to stretch to prevention.

At the regular meeting of council May 21, 1894, bylaw 173 was introduced to establish a dry earth closet system in Newmarket. On the second reading of the bylaw, Mayor Thos. J. Robertson explained it was intended to extend the changes over the whole town but because it would cause some inconveniences, the provisions were limited to 200 feet each side of Main Street from Water Street to Lot Street (Millard Avenue).

Before July 15, 1894, it was mandatory that all privy vaults were to be replaced by dry earth closets or coal ashes in removable boxes. Council appointed a scavenger to remove all excrement at regular intervals at least once a month with a separate uniform charge for hotels, boarding houses, stores and private residences. No privy pit was to be allowed within 50 feet of a well used for drinking water or less than 12 feet from each other.

The eventual construction of a sewer system, water supply and waste disposal were introduced at the beginning of the 1900s. It has been continually refined and expanded compatible with population growth as a fundamental necessity for the health and welfare of the community.

I just got notice there is another big dig — the mainforce twinning project — to improve our water system and plan for the future.

The number of people who perished during the mid-1800s up to the 1930s is quite frankly unbelievable. As I said, one only needs to take a stroll through local cemeteries to get a sense of the loss of life due to a lack of sanitary conditions and a safe water source.

One only need look at the number of people who perished during the Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1917 to get an inkling of what early Newmarket was like.

Our ancestors needed to be hearty in every sense of the word. Their world was not a paradise by any stretch of the imagination.

Sources: The History of Newmarket by Ethel Trewhella; The Newmarket Era; York County Health Records; Disease and Epidemics of the 1800s; Interviews with George W. Luesby Senior – Luesby Memorials

*******

NewmarketToday.ca brings you this weekly feature about our town's history in partnership with Richard MacLeod, the History Hound, a local historian for more than 40 years. He conducts heritage lectures and walking tours of local interest, as well as leads local oral history interviews. You can contact the History Hound at [email protected].