This is the second part of our series on the Davis Tannery, examining the tannery itself and its place in our economic and social history.

Newmarket’s progress seems to quite often be related to either floods or fire. The Canes came here because of fires at their initial location in East Gwillimbury, as we learned in another article. Similarly, a fire at the Davis’s Kinghorn Tannery in King Township resulted in their firm relocating to Newmarket.

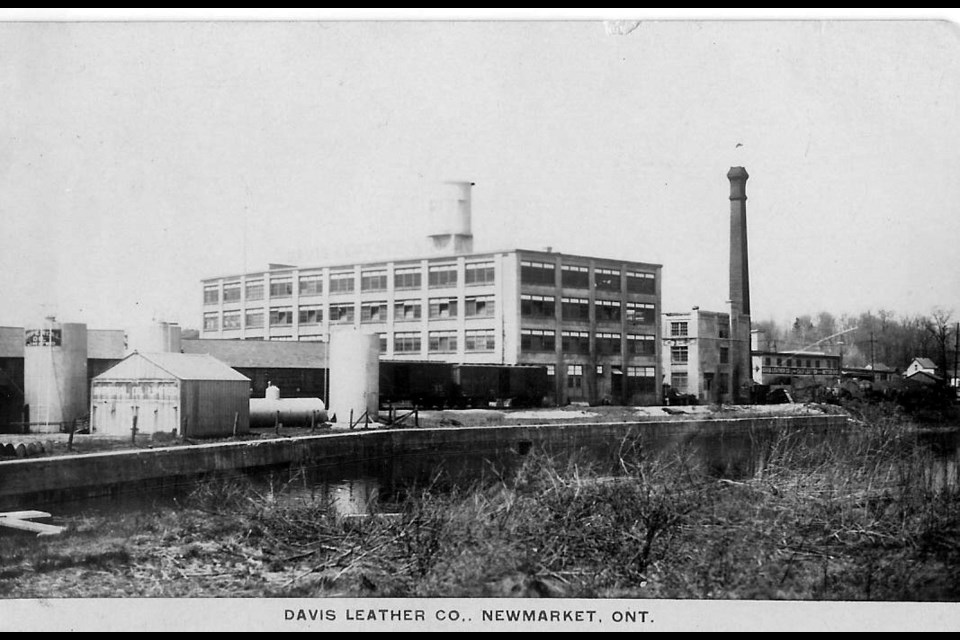

For more than 50 years, the Davis Leather Co. was a mainstay of Newmarket’s industrial component and a force within the community. Their business strength was drawn from the specific business acumen of each of the members of this family enterprise (see the article on the Davis family). The family controlled every phase of the operation.

They prospered in an era of ramped free enterprise with favourable export / import tariffs with Great Britain and few governmental regulations on the environment and wages. Perhaps they may not have prospered in today’s social environment.

There were few female employees until the 1940s. They worked a six-day work week with 10-hour shifts for a wage of $1 per hour up to the First World War. Just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, the work week was 48 hours for a salary of $17 to $25 per week.

There were no social benefits, mandatory retirement, sick pay, paid vacations or pension plans. This was the norm for the period. However, many employees spent their life with the Tannery, beginning in their teens and finding lifelong employment.

The Davis family had emigrated from Wales, establishing themselves on the eastern seaboard of the U.S. before emigrating to Canada after the War of Independence in 1792. William Davis, along with his family of seven, moved to Wentworth County near Hamilton.

The two Davis men of interest for this story are Andrew Davis, great grandson of William, and his cousin, Elihu Pease (brother-in-law to Andrew). Andrew learned the tanning business from his father, James, at a tannery at Sheppard Avenue and Yonge Street (near Newtonbrook Plaza).

In 1847, Elihu Pease purchased 16 acres at Kinghorn on the east branch of the Humber River in King — a match made in heaven, the ample water supply with plenty of hemlock available.

Elihu sold his tannery to Andrew Davis in 1856 and Andrew quickly took his son, Elihu James (E.J.) as a partner, calling the new business Andrew Davis and Son. The firm prospered and was soon shipping its finished product to Toronto by rail. As the surrounding land was cleared, a small steam plant was built to supplement the flow of the Humber River.

In 1884, Andrew retired, and E.J. became sole owner. Just three weeks later, disaster struck and the whole tannery was destroyed by fire. The tannery was soon rebuilt, enlarged to four storeys, doubling the size of the operation. They employed 40 to 50 men and all five of E.J.’s sons were learning the tanning business.

A second fire in March 1903 destroyed everything in an hour. Many would argue that with the destruction of the tannery, the village of Kinghorn would soon die as well. E.J. purchased a tannery in Kingston, sending his two sons, Elmer and Harold, to run it.

E.J. Sr. and his sons, Aubrey, Andrew and E.J. Jr., accepted an offer from the Town of Newmarket council and built a new tannery between the rail tracks and the river on Huron Street (Davis Drive).

In January 1904, Mayor H.S. Cane would deliver an offer to Davis Leather to relocate to Newmarket, offering as an inducement a free water supply, fire protection and railway facilities.

You will remember Mayor Cane had seen the construction of a new waterworks system in the 1890s and this was now an incentive in the bargaining. In addition, a bonus of $10,000 and an exemption from municipal taxes for 10 years was tabled.

The Davises agreed to establish a plant of at least $40,000 in value, employ 75 to 100 men, and continue in business for at least 15 years. A vote was taken locally and accepted by all parties in February 1904.

A new 190 ft. by 182 ft. building was put into operation in January 1905, employing 80 men. Three framed houses were built and placed on Huron for employees. Of interest is the fact that after the opening, rents increased from approximately $2 to $7 per month due to the scarcity of accommodation locally for the employees and their families.

When Andrew Davis and Son moved to Newmarket, it changed its name to the Davis Leather Company. New machinery promoted the output from the factory, and hemlock bark was replaced in the process with commercial chemicals (arsenic). The Kingston tannery specialized in heavy leather products, while Newmarket produced high-grade fine calf leather products.

Both enterprises expanded rapidly and in 1912, a four-storey addition, 80 ft. by 190 ft., doubled the capacity of Newmarket. A fixed assessment of $20,000 for a 10-year period was passed with the agreement that the expansion be at least $50,000.

By 1915, there would be 200 men employed with branch warehouses in Quebec and Boston. Davis Leather would become the largest producer of calf leather in the British Empire with markets around the world. Even during the Depression, 4,000 skins a day in more than 121 colours were processed by the tannery’s 350 employees.

If you read part one of the series, you will remember that the last of E.J. Sr’s son, E.J. Jr., retired from the firm in 1945 and the firm was sold to James H, Gairdner, a Toronto businessman. None of the later generations were interested in the family firm. In 1946, the firm was reorganized and made a public company. By 1948, management dividends on common shares fell to nothing and interest on preferred shares ended in 1954.

The decline of the firm was rapid after 1958 and, by 1961, the firm lost $430,725 and was sold to Boston tanners. In June 1962, all 125 current employees lost their jobs. All the machinery was sold off by March 1969.

After the closure of the leather production in 1962, the building remained vacant except for short periods when small enterprises used parts of the building — Pop Shop, an automotive repair place, Peel Fence Co. and the like.

It was not until September 1985 that the sound but largely derelict building drew the attention of Alberto DoCouto, a Downsview-based developer. He approached council with a proposition for a $6 million shopping mall development, restoring the 114,000 sq. ft. shell.

In November 1985, the property, along with an additional four acres, was purchased and in January 1986 the restoration started. By 1987, there was an 85-store complex with offices, two restaurants, a supermarket and a four-story atrium. The opening in the marble-pillared complex was held on Oct. 28, 1987 with great fanfare. DoCouto paid actress Brooke Shields $25,000 to fly in by helicopter and cut the ribbon for the opening.

The GO Transit depot moved from across the street to become part of this new attraction.

Alas, after 15 years, the building went from a retail centre to a series of government offices, training schools and provincial offences court.

GO Transit built a new depot at Green Lane, a new depot is proposed for Mulock Drive, so who knows what the future may bring.

If you have memories of your own, please post them. Be sure to check out all the photos posted.

Sources: The Newmarket Era; The History of Newmarket by Ethel Trewhella; Stories of Newmarket by Robert Terence Carter; Newmarket Centennial 1857 – 1957 by Jack Luck; Newmarket Progress by the Pioneers (Development and Evolution) by George Luesby; The History of Early Industry in Newmarket by George Luesby

***************

NewmarketToday.ca brings you this weekly feature about our town's history in partnership with Richard MacLeod, the History Hound, a local historian for more than 40 years. He conducts heritage lectures and walking tours of local interest, as well as leads local oral history interviews. You can contact the History Hound at [email protected].