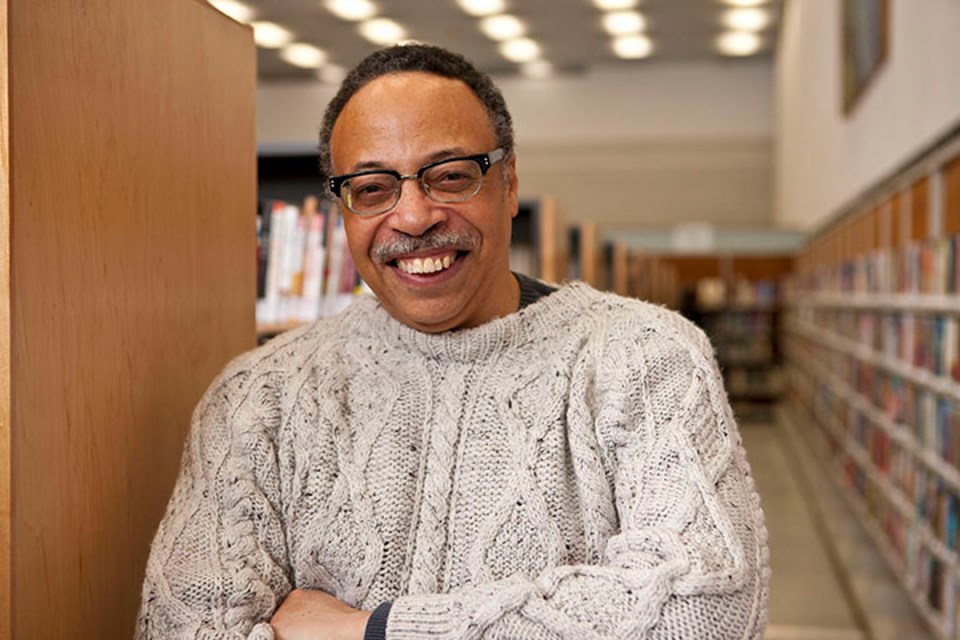

George Elliott Clarke has written extensively about his father.

The award-winning writer and poet, who served as Toronto’s Poet Laureate from 2012 to 2015, has often found inspiration in his life, growing up in Nova Scotia’s Black community.

But in a new memoir covering the first two decades of his life, Where Beauty Survived, Clarke brings a very personal story to light – warts and all – in an examination of Black excellence and the impact it can have on a complicated family dynamic.

Clarke brings his story virtually to the Aurora Public Library (APL) Thursday, Feb. 3 at 7 p.m. in a special evening of discussion over Zoom.

“I have written quite a bit about my father, even in terms of fiction, but never really talked about my mom,” says Clarke. “It was a good time to reflect upon her life and the challenges she faced, as well as her accomplishments, which were prodigious for a Black woman of her time.”

Talking about yourself can be a difficult task, and indeed this was the case for Clarke who threw out his first draft. His long-time editor tasked him with narrowly focusing on the first 20 years of his life – but that too was difficult.

“It’s hard because you’re trying to balance how much of yourself are you willing to expose? How many warts? How many wounds do you want to put before the general public? What is the potential lesson being gathered from displaying those stitches, cuts and bruises – not just of one’s own doing, but rather those that impact the family, one’s parents, one’s siblings, friends, lovers, girlfriends, boyfriends. How much of anyone’s life can you really afford to talk about frankly?

“There’s a lot there, and a lot of private stuff is made public, not for the sake of trying to parade all my sins, faults and crimes of omission, but to talk about how I became a poet. I try to explain how I developed the interest and what was behind the psychology that made me decide as a 15-year-old on July 1, 1975 that I was going to be a songwriter and in short order, only a few months later, I understood in order to be a good songwriter I had to be a good poet.”

In following his dream he contended with what he describes as the dynamic of “folks who are Black coming from the framework that many of us on Turtle Island come from: a history of slavery and enslavement and/or colonialism and imperialism, that our ancestors had to go through hell in order to survive, in order for their descendants to have a chance in order to be successful, to triumph, and to meet what other challenges life might offer… and to face them vigorously, imaginatively, and to overcome.”

Both sides of his family descend from former slaves whose children and grandchildren eventually came to Nova Scotia for better lives. They thrived in the province. His great-grandfather becoming a preeminent African-Canadian Chaplain during the First World War, eventually becoming a radio pastor regularly reaching audiences of 1 million down the east coast of Canada and the United States.

His great-grandfather, in turn, raised a number of notable achievers, including Portia White, who was the first African-Canadian to achieve international stardom in the 1930s.

“As a child growing up in the 1960s in Halifax, these were the people we were connected to. Therefore, much was going to be expected of us; we couldn’t afford to become delinquents, hoodlums, or anything of that sort. We needed to be on the straight and narrow and look to achieve, or at the very least be responsible, respectful citizens, holding up the family honour,” he says.

“That was all great, but there is a downside to that too: sometimes, as I saw in looking at my extended family, the pressure to achieve and the pressure to excel and the pressure to prove that you are as good as anybody in society by essentially showing that you are better than they are in a whole lot of realms – athletics, art, worship and faith, or politics… the pressure to be better than others, the pressure to excel can also have a deleterious impact on family feelings. It can cause division, separation, suffering. That is the other side of the coin.”

Much is written today, he says, on the subject of Black Excellence, but Clarke says he believes young Black people – and younger people in general – might not appreciate how important these early trailblazers were in establishing this idea “when the obstacles facing them were far greater than what the obstacles facing us now may be.”

His father, despite his “great intellect”, was unable to translate these skills into work that was “commensurate with his talent,” he says. It was frustrating and he took this frustration out on his wife and family.

“Even though my father was a working-class man, my mom was a teacher and so they were a good match in that sense,” he says. “We benefited from having parents that were very cosmopolitan in their outlook, making sure we understood the world was far larger and far more fantastic than simply our household, simply our neighbourhoods, simply Halifax, Nova Scotia and Canada. There was a big world full of exciting, interesting dynamics and art-making that was available to us. That was such a fundamentally terrific inheritance to receive from them which I try to pass on, with the help of her mum, to my daughter.”

Next Week: These cosmopolitan influences set George Elliott Clark up to blaze his own trail.

For more on Where Beauty Survives at the Aurora Public Library, visit aurorapl.ca.

Brock Weir is a federally funded Local Journalism Initiative reporter at The Auroran