I am often asked about the entertainment our ancestors enjoyed when they were children, so I thought this week I would highlight the travelling circuses and the magic they brought to town, and next week, I will discuss fairs and the chautauqua.

The travelling circus became a major attraction in the surrounding area about the 1890s. We do not know when the circus first appeared in Newmarket but we do know they usually came once every two years during the first 25 years of the 1900s.

The local merchants loved the arrival of the circus as the advance booking agents would arrive beforehand to secure all the bread, meat and vegetables that they could for the day the circus arrived. Large orders of grains and oats were also placed with the local feed mills, a boom to the local economy, undoubtedly.

These agents would cover the town in colourful, eye-catching signs and on billboards throughout the town. You would also find these brightly lithographed signs featuring ferocious-looking animals in many store windows and on mailbox and fire alarm signal boxes.

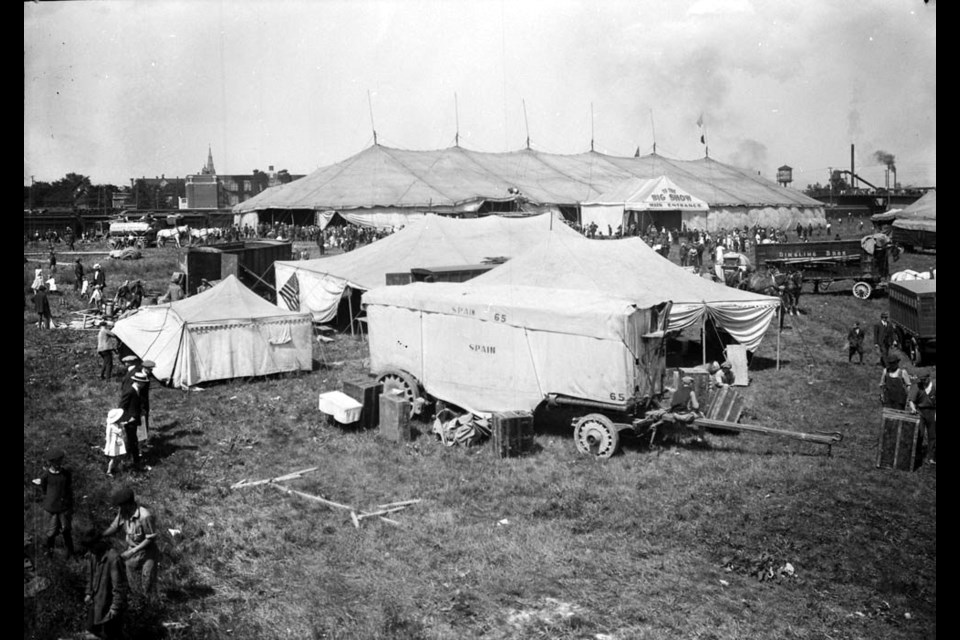

The circus usually owned its own rolling stock, and the day before, a special train would roll into town and be shunted onto a siding near the train station.No machines were used to set up the many tents — all the work was done by manpower or by horses.

A team of four horses would be hitched to each heavy wagon and unloaded from the train in a pre-sequenced order. The wagon holding the three long central poles and stakes was always the first to be unloaded. Next came the wagons containing the crews, generally Black workers, who erected the various tents.

The canvas tents, ropes, grandstand seats and cookhouse stoves, tables and chairs were the next items to be unloaded. Each of the wagons were covered and decorated with carvings of jungle animals and gold paint. As each wagon was unloaded, it was marshalled back to the rail station where it sat in readiness for the grand parade along Main Street to take place later.

The circus was always held in the Specialty flats (currently the River Commons area) and it became the place to be once the circus arrived. Mr. Elman Campbell remembered that each of the three main tent poles was around 30 feet in length and 10 inches in diameter.

Several metal collars were placed near the top of each pole and to these the many rings and pulleys were attached, used to hoist the canvas in addition to supporting various ropes used by the acrobats and trapeze artists.

At the top of these poles was usually a three-foot segment used to fly the Union Jack and Canadian Ensign.

After the circus captain marked the location for the poles, the work crew (usually six-man teams) would drive in six-foot stakes with sledge hammers. These stakes would be used to secure the ropes holding up the main tent.

The canvas was spread out on the ground while the lacing was done, and the buckling put together to hold the Big Top up. Seats were then assembled and more stakes driven into the ground as support for the runners.

Amazingly, there were no nails used in the process. They tell me that there was always a three-ring tent, with red seats placed in the centre and blue seats at either end.

Once the main tent was in place, the crews would then move on to erect the smaller tents. One tent would contain a Wild West rodeo and several smaller side shows. There was always a tent set up as a blacksmith’s shop, with a portable forge, where horses could be shod, or the needs of the circus could be taken care of onsite.

There was always a cookhouse and dining area for the crew. There were tents that sold ice cream and lemonade. Tents to the side of the main tent were used by the families of the performers, rather than having them bunk on the circus train. By noon, all was usually complete, and the crew would sit down to enjoy a well-deserved hot dinner.

It was only at this point that the wagons containing the wild animals would be unloaded from the train. Today we would be appalled, but at that time the idea of carrying jungle animals, monkeys, giraffes, camels and zebras from place to place was accepted. There would be three or four elephants to lead the parade of animals.

We can’t forget the calliope, a musical instrument operated by a keyboard, which in turn controlled a series of whistles under steam pressure, that was a large part of every parade.

The clowns were, of course, the stars of the whole show. The parade would begin at the north end of Main Street and continue its length. After the parade, the animals were taken to the big tent and placed along one wall, in plain sight of all those in attendance. The elephants and herbivorous animals were tethered to stakes only a few feet from the audience.

The show was very much like those we still see on television and in old movies; performing seals, aerial acts and clowns. The young girl doing somersaults on the back of a moving horse was a crowd favourite.

There was a huge watering trough positioned at the corner of Prospect and Queen streets where the elephants and horses were watered twice a day.

The Black workers never remained at the circus once the tents were erected and returned to their quarters on the circus train. They would return once the show was complete and it was time to dismantle and return everything to the wagons.

By early the next morning, everything would be gone without a trace. The grounds were usually left immaculate, not even a scrap of paper or a pile of droppings from the animals. The train was on its way to its next destination and we waited for their next appearance in a few years.

Sources: Remembrances of Elman Campbell; History of Newmarket by Ethel Trewhella; The Circus Comes to Town – Ringling Brothers Circus Story; Oral Histories conducted locally.

************

NewmarketToday.ca brings you Remember This?, a weekly feature about our town's history, in partnership with Richard MacLeod, the History Hound, a local historian for more than 40 years. He conducts heritage lectures and walking tours of local interest, as well as leads local oral history interviews. You can contact the History Hound at [email protected].