My life has been a series of mysterious coincidences lately. Coincidences that seem to wash up on the shoreline of my deepest thoughts like mystical life rafts waiting for me to get in. They enter my domain to provide almost supernatural conclusions to things that have been troubling me.

For example, recently, I was asked to mentor a couple of Indigenous university students as they develop a project that will see them interpret the Indigenous worldview through art.

I was asked to provide guidance to them as an elder. I gladly accepted. It helps that I have known these two brilliant young women for a few years now and our paths keep crossing like rivers flowing with intent.

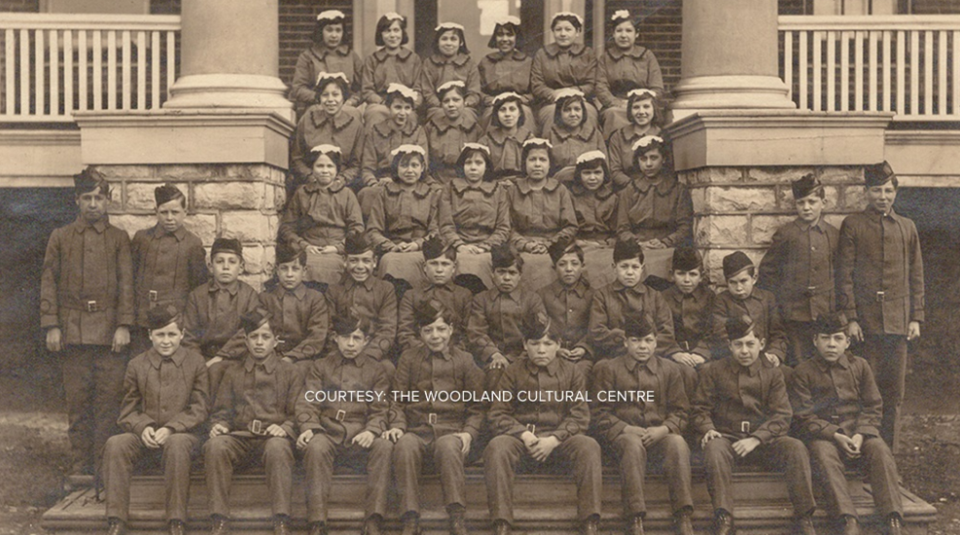

Multiple days prior to meeting these brilliant young minds virtually via Zoom, my mind had been on terminology that was used by my mother’s teachers when she attended residential school at the Mohawk Institute in Brantford, Ontario. In order to belittle the Indigenous students, the teaching staff, would refer to them as 'Bush Indians.'

To be called a Bush Indian was an insult to one’s intelligence. It was used to reform/assimilate these young Indigenous children. It was used so that they might better accept the ways of the larger society by avoiding being labelled a Bush Indian.

It was such an effective tactic that eventually the students were using it on one another to denote that someone was less intelligent. My mother told me that they themselves would use the term on the new kids who were brought to the institute: the uninitiated.

I thought about how demoralizing that would be on impressionable young minds.

So, on the day of our Zoom meeting, the young women related how they would approach their project. They needed my guidance as they wanted to learn of the natural medicines that our ancestors harvested from the land, on this, our traditional territory.

“We want to learn to become good Bush Indians,” one of them joked.

That phrase attained full revolution from what I had been opining on for days prior. I hopped aboard this mystical life raft and engaged them in a discussion on the term Bush Indian.

We discussed how a Bush Indian would have been very knowledgeable of the bush. The Bush Indian would have carried knowledge that the teachers at residential schools would not have possessed.

Bush Indians would still have been lucky enough to carry their Indigenous language(s). That language would have contained a worldview that would have given them an advantage in trying to survive in the natural environment.

They would have known that the cedar tree carries a medicine that wards off the flu and the common cold. They would have known that a successful hunter and fisherman was the quietest, and stealthiest one. They would have known that certain birds can lead you to a successful hunt or that the bass begin to spawn when the red maple shows its beautiful red leaves.

The Bush Indian would have known their connection to everything around them in the natural world. They would have known how we are all connected spirits, learning to live in harmony.

Amazingly, all of that knowing was eliminated, destroyed, within that child with the co-opting of the term, Bush Indian, by residential school staff.

The term was still being used on us as I was growing up. And as we became more assimilated, we used it on one another, just like our parents had at residential school.

“That’s who those children were!” the young women declared in unison. “And that’s who I want to be! A Bush Indian!” they said.

They asked that I teach them about the medicines and their place in the natural world. And I will. Because I too, am a Bush Indian.

Jeff Monague is a former Chief of the Beausoleil First Nation on Christian Island, former treaty research director with the Anishnabek (Union of Ontario Indians), and veteran of the Canadian Forces. Monague, who taught the Ojibwe language with the Simcoe County District School Board and Georgian College, is currently the superintendent of Springwater Provincial Park. His column appears every other Monday.

.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)